Chapter 1 – Lessons from Vietnam Vets

The Body Keeps the Score 2. Yesterday I started reading The Body Keeps the Score and keeping a journal of what touches and triggers me as I read.

I’ve just finished reading Chapter 1. I’m tense, shaking, anxious. My brain feels like mud. And grief is battering at my dam of numbness. It’s a terrible and odd sensation. My instinct is to turn away from it. To keep the grief at bay no matter the cost. For an endless few moments tears stream down my face, and then my brain does what it always does.

“It’s not that bad. You had a good day. Focus on that. Grief will come later.”

And with that the dam is firmly in place again. Firmly in place, but a little weaker than before. My body remains tense, and I’m still shaking and anxious, but at least the overwhelming grief is subdued again.

Today Was A Good Day

Trivialization is not just a covert trauma of mine, it’s also become a defense mechanism. Unlike most people I know, I’m deeply aware of my defense mechanisms. They’ve not been unconscious reactions to me for decades. But my awareness of them doesn’t mean much. I also know that by trivializing my own emotions and reactions I’m harming myself in the long run. Even if it helps me survive in the now.

How was today a good day? I went to a business meeting with two of my cohorts. Thanks to them I managed to function for an hour and a half, without letting my anxiety dull my senses. Or stop me from saying what needed saying. Without censoring myself or disregarding my core values, despite that being the norm when doing business in Aruba.

After that I fitfully slept for 3 hours while my dogs watched over me and cuddled close for comfort. That’s my reality. These interactions are exhausting to me on so many levels.

Then I tried to explain to someone that I wasn’t ‘doing too much.’

Compared to what I used to handle, what I do these days is peanuts. The only difference is that now I’m cognizant of my lack of safety within myself. And that the effects of denying that for 40 years have caught up to me. I used to be just as affected in the past. I was just very good at suppressing it.

The Past Informs the Present

It’s something I really cannot explain to people who have not been affected by trauma or are still in denial about how much past trauma affects them in their day-to-day.

Because my past was encroaching on my present, I went and took the dogs out for a walk. Monroe on the leash, while Azula roamed free. Trying to control a dog that’s more than half my own weight requires being in the present.

Beginnings are hard

So, with renewed courage I’m re-reading the chapter and marking the passages that have shaken me so much. The general feeling of this chapter is that it’s incredibly confronting. It’s eerily familiar to me on a deeply personal level. It touches me not only when it comes to specific issues related to PTSD, but also where it concerns generational trauma. Lack of resources and research for specific trauma-types.

Why listening to patients matters. The very prevalent theme that people instinctively turn away from stories concerning trauma, especially those closest to home. Trauma and the loss of self, numbing, shifts in perception and loss of imagination due to trauma.

Diagnosis and comorbidity issues, and organizations being blind to what’s right in front of their noses. Textbooks that spout a bunch of nonsense, and the horrifying discrepancy between guesstimates and reality.

Four and a half decades later

The worst part? It’s been 45 years since Bessel van der Kolk started working at the VA and began his work on trauma and trauma recovery. Yet in the present I’m running into the very same things. And maybe that’s what touches me most. He started his work at the VA in July 1978, two months after I was born. He has spent his lifetime trying to understand and improve the lives of people like me. And yet, until now, I’ve met very few mental health professionals that have managed to convey a fraction of what van der Kolk has imparted in the space of one chapter.

For some reason that’s making me furious right now. So instead of continuing to write I’m going to let this piece rest, and pick it up again tomorrow.

May 5th, 2023

The Blind Leading the Blind

The Chapter starts with van der Kolk’s first day at the VA in the beginning of July 1978. He’s hanging up a reproduction of Breughel’s “The Blind Leading the Blind” (De Parabel der Blinden). It’s a Dutch masterpiece that has inspired many for a variety of reasons.

I just published a piece on human rights, in which I refer to people’s need for ‘an eye for an eye’ when it comes to justice. As well as what I personally feel about it – which is:

“An eye for an eye will leave the whole world blind.”

M.K. Ghandi

In the land of the blind, the one-eyed is King

It also ties into another Dutch saying I use frequently: “in het land der blinden, is eenoog koning” (in the country of the blind, the one-eyed is king). It’s a saying I use mockingly. It means that if someone has a little knowledge they’re considered an expert by people who don’t possess that knowledge at all. It’s something I’ve run into all over the world. The ‘authority’ in these cases are treated as kings, even when their pearls of wisdom are not founded on facts. Let stand the latest studies or available information.

It’s a double edged sword for me. I’ve often been allowed to explore subjects or hone skills because there was no authority in a lot of situations. On the other hand, I’ve also encountered plenty of ‘authorities’ who took up the mantle all too easily. By doing so caused harm due to their lack of knowledge. Yet were not held nor felt accountable because they were considered the best there was in that particular setting.

In small communities with limited resources, such as Aruba, it’s often par for the course.

PTSD and Generational Trauma

“Tom went through the motions of living a normal life, hoping that by faking it he would learn to become his old self again. He now had a thriving law practice and a picture-perfect family, but he sensed he wasn’t normal; he felt dead inside.”

“The Body Keeps the Score: Mind, Brain and Body in the Transformation of Trauma” by Bessel van der Kolk

Van der Kolk describes meeting his first veteran, Tom, and some of the things Tom was experiencing. He also describes why Tom’s story was familiar to him. Within his own family van der Kolk recognized certain behaviors and emotional reactions. Later on van der Kolk indicates that Tom’s story, behavior and emotional reactions are similar to those of other vets. As well as victims of sexual abuse.

Besides the obvious familiarity between my own experiences with PTSD, the generational trauma aspect has struck a nerve. I consider this type of trauma a complex trauma. I’m writing two articles on this subject. The first, generational trauma, is something I am quite familiar with myself. As well as something I’ve witnessed in a lot of families. The second article will be about racial trauma and its effects. That one requires a lot of input from local sources. Post-colonial societies and societies that have a slavery past deal with racial trauma on a daily basis. But most people are unaware of the widespread effects or their own roles in it.

Patients as Textbooks and Lack of Literature

“Kardiner’s description corroborated my own observations, which was reassuring, but it provided me with little guidance on how to help the veterans. The lack of literature on the topic was a handicap, but my great teacher, Elvin Semrad, had taught us to be skeptical about textbooks. We had only one real textbook, he said: our patients. We should trust only what we could learn from them—and from our own experience. This sounds so simple, but even as Semrad pushed us to rely upon self-knowledge, he also warned us how difficult that process really is, since human beings are experts in wishful thinking and obscuring the truth. I remember him saying: “The greatest sources of our suffering are the lies we tell ourselves.” Working at the VA I soon discovered how excruciating it can be to face reality. This was true both for my patients and for myself.”

“The Body Keeps the Score: Mind, Brain and Body in the Transformation of Trauma” by Bessel van der Kolk

These days there’s plenty of literature, but seemingly little consensus. In the past 4 years I’ve collected so much data, but a lot of that data is difficult to corroborate. Or things which have already proven to be untrue, or taken out of context, keep turning up as factual, or even ‘the only’ truth.

As to listening to patients: right before starting on this chapter I had just read an article about a doctor who almost died because his own doctors didn’t listen. And for the past 4 years I’ve run into the same thing myself. It’s incredibly frustrating.

Looking The Other Way

“We don’t really want to know what soldiers go through in combat. We do not really want to know how many children are being molested and abused in our own society or how many couples—almost a third, as it turns out—engage in violence at some point during their relationship. We want to think of families as safe havens in a heartless world and of our own country as populated by enlightened, civilized people. We prefer to believe that cruelty occurs only in faraway places like Darfur or the Congo. It is hard enough for observers to bear witness to pain. Is it any wonder, then, that the traumatized individuals themselves cannot tolerate remembering it and that they often resort to using drugs, alcohol, or self-mutilation to block out their unbearable knowledge?”

“The Body Keeps the Score: Mind, Brain and Body in the Transformation of Trauma” by Bessel van der Kolk

This is something most people I know who have suffered from trauma experience. For me personally it is one of the hardest aspects of my life. To this day I self-censor when it comes to my traumatic experiences because I’ve learned that talking about them is taboo. That talking about them makes people react defensively in a plethora of ways. And most of those ways are painful for me.

In certain cases I’ve stopped trying all together. And then get accused of not talking or communicating enough. When I try to explain that the reactions I’ve gotten in the past have taught me to remain mum, these people feel as though I’m attacking them personally, no matter how neutral I try to remain in what I say. And things just escalate.

There are exceptions to this rule. And those people have helped my road to recovery tremendously. Oddly enough almost none of these people are mental health professionals. I’ll write about this in a separate post one day.

Trauma and the Loss of Self

“After you have experienced something so unspeakable, how do you learn to trust yourself or anyone else again? Or, conversely, how can you surrender to an intimate relationship after you have been brutally violated? “

“The Body Keeps the Score: Mind, Brain and Body in the Transformation of Trauma” by Bessel van der Kolk

This is something I’ve struggled with for most of my life. And at times, fall prey to. I did learn at an early age that I need to trust and be vulnerable in order to experience real connections. In some cases I try to follow the rule “trust, but verify,” which I still can’t implement consistently. I dislike the verification part, even when rationally I know it’s often necessary. Especially in societies such as Aruba. To me it still feels like the antithesis of trust.

Surrendering to an intimate relationship was initially hard for me, especially physically. But oddly enough I realized at a certain point that if I didn’t surrender, I’d be giving my abusers another ‘victory’. From that moment on for me personally, physical intimacy became not just a wonderful, human connection, but also a personal victory over my own traumas.

Allowing yourself to remember

“It takes enormous trust and courage to allow yourself to remember. One of the hardest things for traumatized people is to confront their shame about the way they behaved during a traumatic episode, whether it is objectively warranted (as in the commission of atrocities) or not (as in the case of a child who tries to placate her abuser).”

“The Body Keeps the Score: Mind, Brain and Body in the Transformation of Trauma” by Bessel van der Kolk

This is one part within myself I’m a little bit proud of. I honestly can’t tell when I learned how to do this or why. It’s not so much that I no longer feel the shame, but more that I’ve accepted that I made a choice to survive, and there is no judgement in that choice. That I cannot convey to others how this works at times has led to rather bizarre situations. Especially with mental health professionals. According to them, I should feel a whole boatload of things, which I don’t anymore. Or when I do, those feelings don’t last very long.

The best I can do is refer to a quote from a book I read as a kid, and still reread every few years.

“Think of all those experiences, the wisdom they’d bring. But wisdom tempers love, doesn’t it? And it puts a new shape on hate.”

-“Dune” by Frank Herbert

To me understanding brings acceptance. And acceptance softens feelings. It doesn’t mean I condone or accept what’s happened. Just that I accept that in order to survive I had to play a role, a part. It was me. But just a small aspect of me. Not all of me.

Numbing

“Maybe the worst of Tom’s symptoms was that he felt emotionally numb. He desperately wanted to love his family, but he just couldn’t evoke any deep feelings for them. He felt emotionally distant from everybody, as though his heart were frozen and he were living behind a glass wall. That numbness extended to himself, as well. He could not really feel anything except for his momentary rages and his shame. He described how he hardly recognized himself when he looked in the mirror to shave.”

“The Body Keeps the Score: Mind, Brain and Body in the Transformation of Trauma” by Bessel van der Kolk

The section on numbing was one of the hardest for me to read. Especially this part:

“When he heard himself arguing a case in court, he would observe himself from a distance and wonder how this guy, who happened to look and talk like him, was able to make such cogent arguments. When he won a case he pretended to be gratified, and when he lost it was as though he had seen it coming and was resigned to the defeat even before it happened. Despite the fact that he was a very effective lawyer, he always felt as though he were floating in space, lacking any sense of purpose or direction.”

“The Body Keeps the Score: Mind, Brain and Body in the Transformation of Trauma” by Bessel van der Kolk

Why is this particularly hard? I think because I recognize myself in this so strongly, yet cannot convey this to people except those who have experienced PTSD themselves. To most people the fact that I can make cogent arguments means I can’t be mentally ill. And for a time a part of me agreed with them. As I’ve written before, being mentally ill does not mean you can’t be rational or eloquent, nor does being rational or eloquent preclude mental illness.

Shifts in perception

“I saw Bill surrounded by worried doctors who were preparing to inject him with a powerful antipsychotic drug and ship him off to a locked ward. They described his symptoms and asked my opinion. Having worked in a previous job on a ward specializing in the treatment of schizophrenics, I was intrigued. Something about the diagnosis didn’t sound right. I asked Bill if I could talk with him, and after hearing his story, I unwittingly paraphrased something Sigmund Freud had said about trauma in 1895: “I think this man is suffering from memories.”

“The Body Keeps the Score: Mind, Brain and Body in the Transformation of Trauma” by Bessel van der Kolk

This I recognize strongly too. For me my flashbacks or memories usually cause me to freeze, tune out and disassociate; my visceral reaction is often missed by people. To this day I still sometimes come out of these episodes with people angrily asking me why I’m not answering or if I’m even bothering to pay attention. It’s hard to explain.

And hard to watch someone else go through.

I’ve seen a lot of people snap like this. And the way they’re treated at such moments breaks my heart. I know a lot of people who have snapped like this, and afterwards are treated like pariahs or handled as though they may break at any moment. All I can say is that for me personally, these reactions are almost worse than the flashbacks themselves. I am more than my experienced trauma. I am more than just my disease.

Loss of imagination

“Imagination is absolutely critical to the quality of our lives. Our imagination enables us to leave our routine everyday existence by fantasizing about travel, food, sex, falling in love, or having the last word—all the things that make life interesting. Imagination gives us the opportunity to envision new possibilities—it is an essential launchpad for making our hopes come true. It fires our creativity, relieves our boredom, alleviates our pain, enhances our pleasure, and enriches our most intimate relationships. When people are compulsively and constantly pulled back into the past, to the last time they felt intense involvement and deep emotions, they suffer from a failure of imagination, a loss of the mental flexibility. Without imagination there is no hope, no chance to envision a better future, no place to go, no goal to reach.”

“The Body Keeps the Score: Mind, Brain and Body in the Transformation of Trauma” by Bessel van der Kolk

The times I am at my lowest, all my imagination has left me. It usually starts with an inability to read, or that I suddenly lose the capacity for creative problem solving.

It’s also part of the reason why I managed to function for long periods of time, despite not being well at all. I’ve read and been read to since early childhood. And through reading I first encountered characters that made me feel less alone in my process.

Getting to know myself through Literature

Writers such as Frances Hodgson Burnett (The Little Princess and The Secret Garden) helped me realize that moving countries and cultures and my experiences in that were not as strange as my environment sometimes made it out to be.

Wilkie Collin’s book “The Moonstone” and Charles Dickinson’s “The Tale of Two Cities” introduced me to the characters Franklin Blake and Charles Darnay respectively. Both characters have been educated and lived in various countries, which is a two edged sword when it comes to their social interactions. I related to them incredibly strongly.

Besides reading, I used to compose, act, direct, write and choreograph. These hobbies were incredibly valuable to me in hindsight, as a means to keep holding on to hope. As I started growing up, and these hobbies were seen as immature or not viable career paths, my mental health also deteriorated.

Loss of imagination as a precursor to poor mental health

When I noticed it was getting hard for me to read again about 8 years ago, I immediately saw it as a sign of an imminent decline. I asked my environment for help in avoiding that. Unfortunately I got little support in that endeavor, and ended up in one of the worst periods of my life. Later on I was told by the people closest to me that they’d assumed I was cured or they hadn’t taken my PTSD diagnosis that seriously, because I was functioning so well.

Reading this particular section has also made me realize that an earlier post I wrote about why I write still remains painfully true.

“So here’s why I write. I don’t want to. I don’t even like it most of the time. It’s confronting and terrifying. It’s triggering. But I need to write. Just to survive another day while waiting for fitting treatment for my disease.”

“Why do I write about mental illness and trauma” – Just Julie

Stuck in Trauma

“Whether the trauma had occurred ten years in the past or more than forty, my patients could not bridge the gap between their wartime experiences and their current lives. Somehow the very event that caused them so much pain had also become their sole source of meaning.”

“The Body Keeps the Score: Mind, Brain and Body in the Transformation of Trauma” by Bessel van der Kolk

This is another example of strong recognition, that I find difficult to explain to those who are not on the road to recovery from trauma. I often hear or read simplified life lessons, that really aren’t helpful to me or others in my situation.

“Time heals all wounds”

“Stop using your past as an excuse”

“Winners never quit”

“Don’t let them win”

“If you can’t beat them, join them”

“Fake it till you make it”

Diagnosis and comorbidity issues

“In those early days at the VA, we labeled our veterans with all sorts of diagnoses—alcoholism, substance abuse, depression, mood disorder, even schizophrenia—and we tried every treatment in our textbooks. But for all our efforts it became clear that we were actually accomplishing very little. The powerful drugs we prescribed often left the men in such a fog that they could barely function. When we encouraged them to talk about the precise details of a traumatic event, we often inadvertently triggered a full-blown flashback, rather than helping them resolve the issue. Many of them dropped out of treatment because we were not only failing to help but also sometimes making things worse.”

“The Body Keeps the Score: Mind, Brain and Body in the Transformation of Trauma” by Bessel van der Kolk

Despite PTSD and cPTSD being defined these days, I and others like me, are still being diagnosed with co-morbid diagnosis. Whether it’s some variation of a personality disorder, an eating disorder or a spectrum disorder, it’s tiring as hell. Especially when these co-morbid disorders only encompass 40% of my symptoms and the other 60% are completely inaccurate in my particular case.

What’s even worse, these co-morbid disorders are the ones I’m offered treatment for. And in my experience, those treatments have consistently made my symptoms worse. Reading that this is has been experienced by others like me since around my birth, just makes the fact that it still happens in this day and age, even more disheartening. Especially since most mental health professionals take my worsening of symptoms as signs of another type of personality disorder, instead of a known reaction when dealing with trauma disorders.

Organizations being blind to what’s right in front of their noses

“The opening line of the grant rejection read: “It has never been shown that PTSD is relevant to the mission of the Veterans Administration.” Since then, of course, the mission of the VA has become organized around the diagnosis of PTSD and brain injury, and considerable resources are dedicated to applying “evidence-based treatments” to traumatized war veterans.”

“The Body Keeps the Score: Mind, Brain and Body in the Transformation of Trauma” by Bessel van der Kolk

Unfortunately this still happens. When I saw the ads for the 34th Annual Boston International Trauma Conference, I immediately inquired if my mental health care provider, Respaldo (Aruba’s National Health Care Provider), would be attending. The answer I got was that if individuals were interested in trauma they were free to attend. Trauma is considered a specialty, and Respaldo’s employees are generalists. Thus attending a trauma conference isn’t considered a high priority. That there are too few patients to warrant attendance except for those who find it interesting for personal reasons.

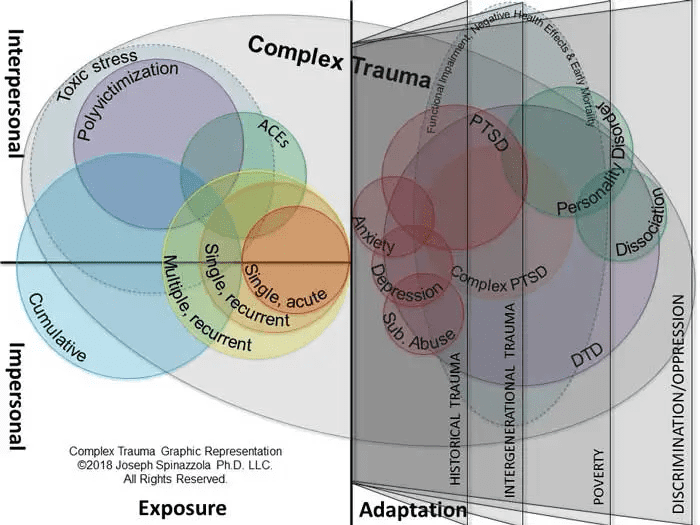

I honestly do not understand this reasoning. This graph shows a representation of complex trauma and the mental health issues it can be an underlying factor in. If it is know to be so prevalent in mental health challenges, why is it seen as a specialty?

Discrepancies in Numbers

“I was particularly struck by how many female patients spoke of being sexually abused as children. This was puzzling, as the standard textbook of psychiatry at the time stated that incest was extremely rare in the United States, occurring about once in every million women. Given that there were then only about one hundred million women living in the United States, I wondered how forty seven, almost half of them, had found their way to my office in the basement of the hospital.”

“The Body Keeps the Score: Mind, Brain and Body in the Transformation of Trauma” by Bessel van der Kolk

This is something I am confronted with on a daily basis. For whatever reason, the traumas I have suffered and my reactions to them are considered rare. Yet over and over again I am now finding out that things which were hailed as ‘true’ 25 years ago, and are still being hailed as true in certain societies today, have been dis-proven, or found to have been lacking. Yet if anyone has a little common sense, like van der Kolk had in this particular case, they’d question the validity of what textbooks say more often.

It reminds me of what one of my history teachers once said. “History is written by the victors.” And victors often have a skewed view of ‘truth.’

“Furthermore, the textbook said, “There is little agreement about the role of father-daughter incest as a source of serious subsequent psychopathology.” My patients with incest histories were hardly free of “subsequent psychopathology”—they were profoundly depressed, confused, and often engaged in bizarrely self-harmful behaviors, such as cutting themselves with razor blades. The textbook went on to practically endorse incest, explaining that “such incestuous activity diminishes the subject’s chance of psychosis and allows for a better adjustment to the external world.” In fact, as it turned out, incest had devastating effects on women’s well-being.”

“The Body Keeps the Score: Mind, Brain and Body in the Transformation of Trauma” by Bessel van der Kolk

Where to start? For Just a Regular Julie I am writing a piece on how to form an opinion on whether articles, studies or news pieces are factual or true. When seemingly informative, factual articles or actually op-eds. It’s something I was taught to do as a young teenager.

Again, as with the case of van der Kolk’s example, common sense seems to be missing when it comes to published work. It’s somehow become ingrained, instead of being an exception.

Some Terrifying Numbers from 2015

“While about a quarter of the soldiers who serve in war zones are expected to develop serious posttraumatic problems, the majority of Americans experience a violent crime at some time during their lives, and more accurate reporting has revealed that twelve million women in the United States have been victims of rape. More than half of all rapes occur in girls below age fifteen. For many people the war begins at home: Each year about three million children in the United States are reported as victims of child abuse and neglect. One million of these cases are serious and credible enough to force local child protective services or the courts to take action. In other words, for every soldier who serves in a war zone abroad, there are ten children who are endangered in their own homes. This is particularly tragic, since it is very difficult for growing children to recover when the source of terror and pain is not enemy combatants but their own caretakers.”

“The Body Keeps the Score: Mind, Brain and Body in the Transformation of Trauma” by Bessel van der Kolk

In 2015 the population in the US was about 320 million. The majority of these will experience or have experienced a violent crime.

4% Of the US population at the time had been a victim of rape. 2% Of the population experienced those rapes before the age of 15.

In 2015 there were approximately 74 million children in the US. That means that 4% of these children were REPORTED as victims of child abuse or neglect. 1 Million – or 1.3% of these reports warranted action from outside sources.

Here’s some numbers when it comes to how many sexual assaults are actually reported in the United States. Only 31% are reported. That’s less than a third. If these numbers are correct, then it’s quite possible that 13% of the US population in 2015 were raped. And that 6.5% of the population was raped before the age of 15. That’s 43 million and 21.5 million women respectively.

How many of the reported sexual assaults led to incarceration? 0.025%. That’s 1 conviction for every 4,000 sexual assaults.

Numbers in Aruba

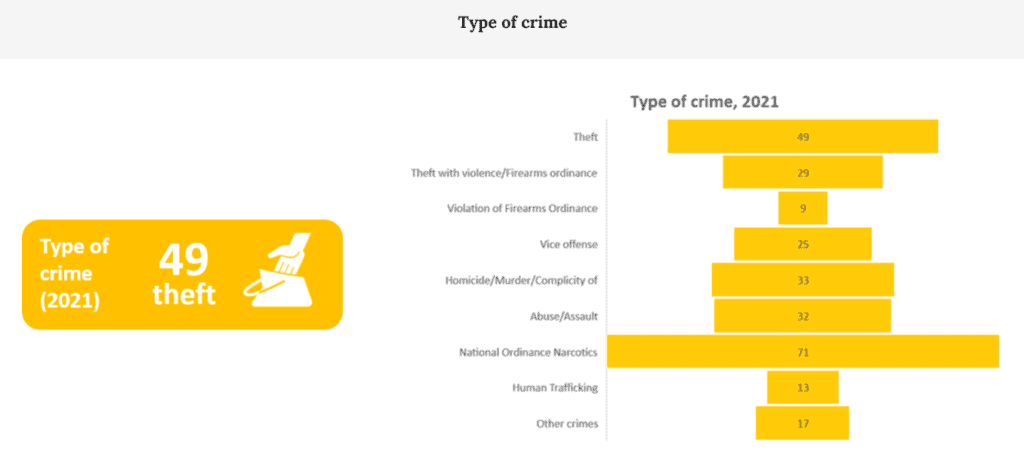

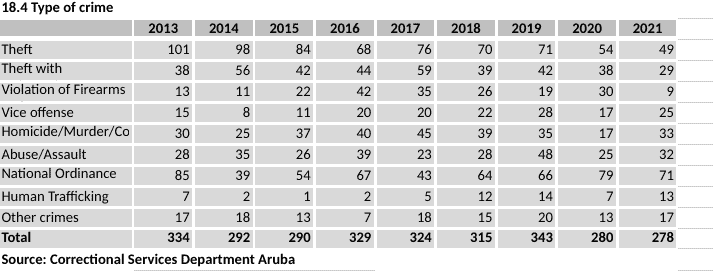

Number of Crime Convictions in Aruba 2021

According to Aruba’s Central Bureau for Statistics the crime CONVICTION numbers in Aruba in 2021 for assault or abuse were as stated above. But wait…these numbers seem to be about crime rates in Aruba. Unfortunately they’re not. The source of these numbers is Aruba’s Correctional Services Department.

Whether abuse or assault includes sexual assault is unclear. I had hoped to find numbers on our local Foundation Against Domestic Violence site, but I can’t find any.

But let’s say for arguments sake that Aruba’s conviction and reporting rate is similar to the US and that of the Abuse/Assault convictions 25% pertain to sexual assaults. 32/4=8. 8=0.025%. 8 x 4,000 = 32,000 sexual assaults in 2021. I’m terrible at numbers though, so I’m sure someone, somewhere will completely debunk these.

Estimated Number of People Requiring Mental Health Care Services in 2020

As I wrote a few weeks ago, the estimated number of people requiring mental health care in Aruba in 2020 was 12,000. That was about 12% of Aruba’s population at the time. How many of these 12,000 are deemed mentally ill, is unknown to me. Nor do I know if these numbers take into account how many people don’t see their doctors even if they do have mental health care challenges. Personally I think that 12% of the population needing mental health care is rather low. Unless those 12% are all deemed mentally ill.

One of the numbers I didn’t mention before: according to Respaldo, at least 2/3 of the population that needed mental health care in 2020, is not receiving it. In my case I wonder if I’m considered to be receiving mental health care, as technically I do have a psychiatrist who does prescribe anti-anxiety medication. Or if I’m in the 2/3 of the population, as there is no fitting treatment for me locally.

A New Understanding

“Since the early 1990s brain-imaging tools have started to show us what actually happens inside the brains of traumatized people. This has proven essential to understanding the damage inflicted by trauma and has guided us to formulate entirely new avenues of repair.”

“The Body Keeps the Score: Mind, Brain and Body in the Transformation of Trauma” by Bessel van der Kolk

For over 30 years brain scans have been made of traumatized people. Yet in the past 4 years, since learning of these studies, I have not been able to get confirmation or denial from my mental health care provider as to the validity of this. I assume they do know, as they’re offering ECT treatments for major depressive episodes according to the 2020 annual report. Yet in all my communications, this option has never even been discussed with me.

“We have learned that trauma is not just an event that took place sometime in the past; it is also the imprint left by that experience on mind, brain, and body. This imprint has ongoing consequences for how the human organism manages to survive in the present.”

“The Body Keeps the Score: Mind, Brain and Body in the Transformation of Trauma” by Bessel van der Kolk

Here again, van der Kolk references that trauma not only leaves an imprint on the mind, but also on the body and brain. This is also something I have been trying to verify with my mental health care provider for years. All my previous treatments have focused solely on the mind aspect. None have dealt with my brain nor body. When I recently inquired about somatic therapy, I was informed none were available, and that the treatment center in The Netherlands offers little in that area too.

In the past the treatments that led to breakthroughs where my PTSD was concerned were all creative or somatic therapies.

“Trauma results in a fundamental reorganization of the way mind and brain manage perceptions. It changes not only how we think and what we think about, but also our very capacity to think. We have discovered that helping victims of trauma find the words to describe what has happened to them is profoundly meaningful, but usually it is not enough. The act of telling the story doesn’t necessarily alter the automatic physical and hormonal responses of bodies that remain hypervigilant, prepared to be assaulted or violated at any time. For real change to take place, the body needs to learn that the danger has passed and to live in the reality of the present. Our search to understand trauma has led us to think differently not only about the structure of the mind but also about the processes by which it heals.”

“The Body Keeps the Score: Mind, Brain and Body in the Transformation of Trauma” by Bessel van der Kolk

This. Just this. I feel like I have been saying this for most of my life. And for most of my life I’ve been told I’m wrong. I’m deathly curious as to van der Kolk’s research and suggestions other than talk therapy, but I’ll practice some self-restraint, and not skip ahead to those chapters!

The Body Keeps the Score 3 – Chapter 2: Revolutions in Understanding Mind and Brain

1 thought on “The Body Keeps The Score 2 – Lessons from Vietnam Vets”